Alex Honnold

No ropes. No supports. No second chances. Free soloing is climbing taken to its furthest extremes and Alex Honnold is the sport’s rock star.

By Sanjiv Bhattacharya

First published by Esquire (UK), Dec 2012

It was 10pm in the black of night in Yosemite National Park, when Alex Honnold felt his first sharp tweak of fear. He saw a mouse.

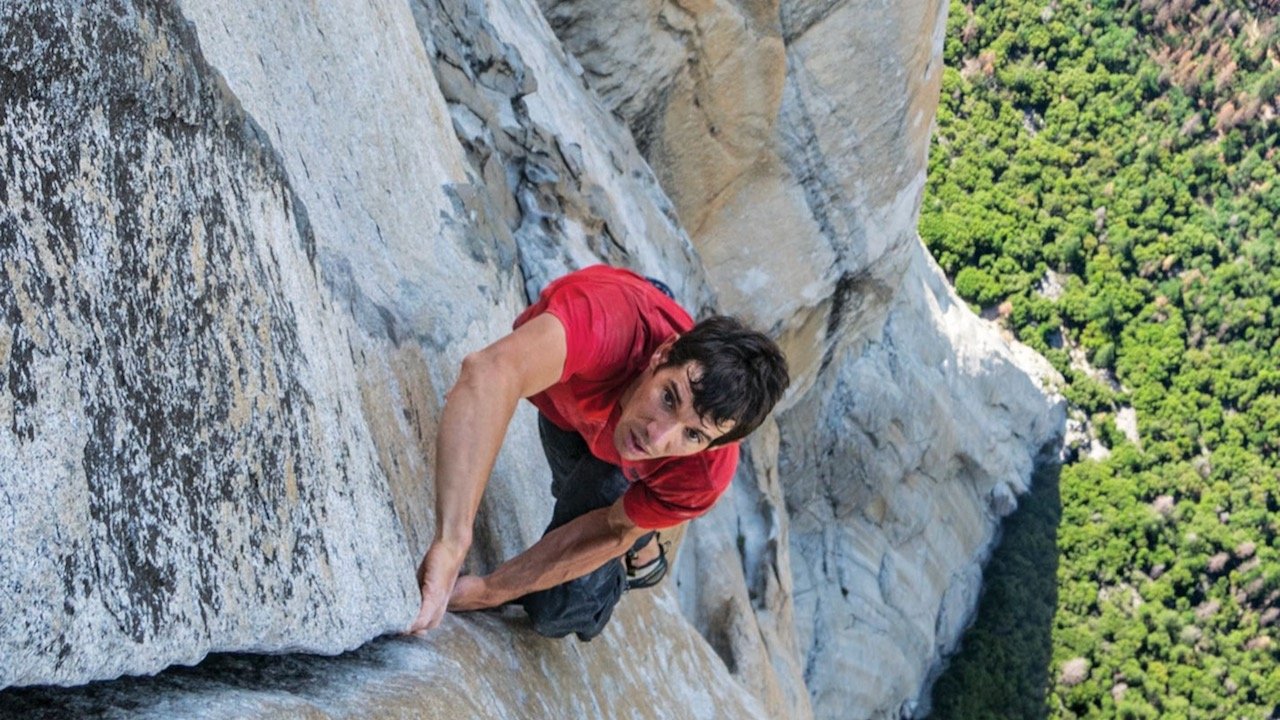

No one would accuse Honnold of scaring easily but he was 400ft up a 3000ft wall at the time, the world famous El Capitan, an imperious sheer cliff of granite, as tall as ten Big Bens. And even though 400ft is a piffling altitude for arguably the best big wall climber of our time, it’ll still kill you if you fall, which is always possible when you’re up there without ropes or aids or a partner, a style known as ‘free soloing’. Not for the first time, Honnold was on the ultimate precipice - one slip, one mishap, one bite from a mouse, and he would die.

“Things were already going wrong,” he tells me later. “The rock was damp because it had dumped rain two days earlier, and I forgot my chalk bag - you need chalk to dry your hands. Also, for climbers, a chalk bag is like a psychological crutch. Whenever you’re nervous, you chalk up.”

Normally, he would have hiked back to the van to get his chalk bag, but that would have taken too long. He was attempting to climb the Triple – the three biggest walls in Yosemite - in 24 hours. And the clock was ticking. He’d started with Mt Watkins (2000ft) at 4.30pm that day, when the wall went into the shade. The plan was to climb El Capitan through the night, and then Half Dome (2000ft) the following morning.

And yet, there he was, alone on a wall in the darkness, sensing his fear flutter up inside him like a flock of birds. His position was awkward. He clung onto a diagonal crack with both hands, with his left foot wedged in below at such an angle that he couldn’t see it, even with a headlamp. The only way forward was this one hold above him, a ‘pod’, the very hold that the mouse had scurried into. And he couldn’t flush him out – he slapped the rock, he whistled, nothing was working.

“I didn’t want to get bitten. My rational brain knew that the mouse was more scared of me than I was of him. But that’s how fear works. When a few little things go wrong, it’s easy to start down that road where you build this escalating sense of panic, like, ‘oh fuck oh fuck oh fuck, I don’t know what to do…’”

It took him thirty long seconds to, as he puts it, “nip that shit in the bud” – to convince himself that the wet walls, the no-chalk, the mouse, none of this mattered. And he went on to make history. He topped El Capitan at 3.30am, free soloing most of it but using aids for the tougher sections. He then hiked down, drove over to Half Dome and scaled that before lunchtime.

It’s hard for a non-climber to appreciate how impressive this is. Rock climbing is an odd and impenetrable sport in many ways. On the one hand, it has the primal simplicity of a man on a wall, and on the other, it’s a niche world of sub-categories and technical lingo. The greatest climbers are virtual unknowns, and the greatest feats are scarcely witnessed by anyone. There’s no Olympic event or national team. And though the sport is old on paper – it began with Victorian mountaineers in the Alps – it feels young and new, in part because successive generations, thanks to better equipment and training, keep raising the bar so dramatically, year upon year.

Honnold’s Triple for instance. For context, any one of these walls would take several days for a skilled climber. In fact, in 1957, it was considered a pinnacle achievement when a team led by Royal Robbins took 5 days to summit the Half Dome alone. As for the Nose Route of El Capitan, the first person to free climb it – using ropes only for safety - was Lynn Hill in 1994, who took 23 hours. Just over a decade later, Tommy Caldwell accomplished Hill’s feat in twelve. To date, the closest anyone has come to Honnold’s Triple was in 2002, when the X year old Dean Potter free-climbed both El Capitan and Half Dome in 23 hours. Honnold speed-climbed all three in 18 hours.

Ask most climbers about Honnold and you’ll hear words like “insane”, “incredible” and “not human”. But whether he’s the best rock climber alive depends on your definition. By his own admission, he’s not the most technically skilled. While some, like Chris Sharma, can climb pitches (sections of a route) that are graded 5.15 in difficulty, Honnold’s limit is 5.14.

But rock climbing tests more than just skill. Unlike most sports, climbers are routinely required to overcome their fear of death, to restrain the galloping panic that can begin when a mouse runs into your hold. And this is where Honnold reigns - he is the world’s foremost free soloist, a style of climbing so pure and terrifying that only a miniscule fraction of climbers even dare to attempt it.

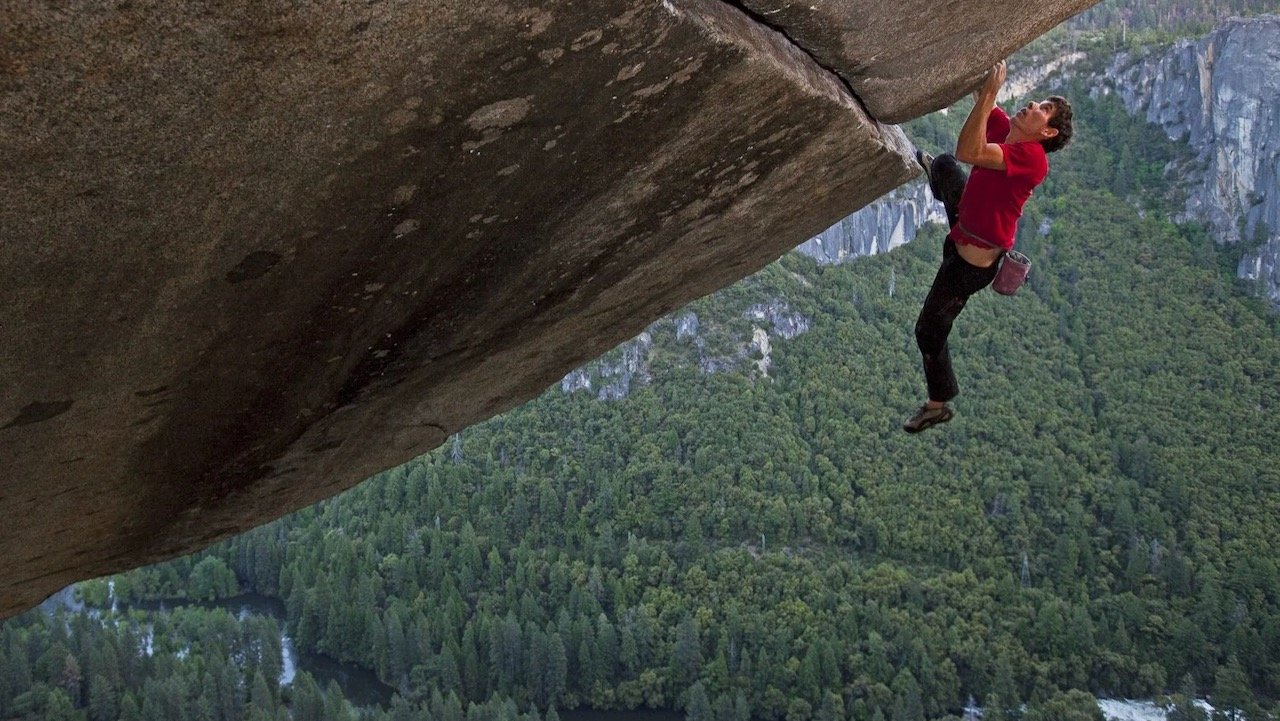

Free soloists climb without ropes – that is, they risk death at every moment. It’s already an irresistible metaphor for a human speck to scale a colossal wall, but when that speck has no safety rope, it becomes something epic and astonishing. Honnold’s most celebrated free-soloing accomplishment was Half Dome in September 2008. No one witnessed it, but when he recreated a moment for Sender Films, in a short film entitled Alone On The Wall, it was so gripping that it led to stories in National Geographic, Outside, and the CBS news magazine show, 60 minutes. Even today, in Yosemite, a Mecca for climbers, people stop him constantly. They whisper as he passes: “did you see who that was?”

In September, Honnold’s fame will only escalate. Sender Films also shot the Triple for a feature documentary, which is expected to make a splash in climbing circles. It will also inch him inexorably towards his next goal, one that he has been talking about for years now – to free solo El Capitan, a feat that is almost beyond comprehension. El Cap is as high as three Eiffel Towers.

“It’s the next logical step, but it’s a pretty freaking big one,” he says. “I’d probably 95% succeed. It’s just, you’d get fatigued – it would take nearly five hours, and a bunch of the hard stuff is up at the top. I don’t know. Someone’s going to do it.”

Race-car drivers and big wave surfers risk death too, but they have at least the illusion of safety - whether it’s helmets and roll cages, or just the knowledge that they’ve wiped out before and survived. There is no such comfort for Honnold. He slips, he dies and he knows it.

“And for surfers, the moments of peril last minutes,” says Peter Mortimer, of Sender Films, who shot Honnold’s Triple. “Alex has to maintain perfect concentration for hours. That’s why free-soloists are so incredible. Climbing is about boldness as well as strength. And Alex’s boldness and vision are on such a level that, for a lot of climbers, he’s the greatest rock climber ever. And he’s only 26.”

A few hours after he finishes the Triple, I meet Alex outside my hotel in Yosemite. We planned to hang out for a few days, so I drove up from Los Angeles. But, typically, he didn’t tell me about the Triple – he never announces this kind of thing until after it’s over. So I have no idea what he’s just done. He just looks like some skinny kid in flip flops, shorts and a hoodie, standing in the car park looking a bit sunburnt and spaced out.

“Dude, I’m like crushed right now,” he says. “I could use some food, but after that I’m going to have to crash.”

As we eat, the enormity of his achievement becomes clear. But I have to dig it out of him. After three days with him, I think Honnold may be the most humble and extraordinary person I’ve ever met. Nothing about him suggests “elite athlete”. His hands are broad, his fingers wide and thick, but other than that, he looks unremarkable – a slim 5’11, 160lbs, with sticky-out ears. He’s intelligent and well read, funny and fluent in the Cali-lingo of “dude”, “heinous”, “sick” and “gnarly”. He’s utterly driven and clean-living – he’s never had a drink because “I don’t see the point” - and he’s apparently unmoved by material comforts. After we ate, that first night, he spent the night on a mattress in a shabby white van in the car park, a van he’s lived in for five years now.

“It’s perfectly functional,” he tells me, pointing to the little gas hob, and the storage under his bed. There are climbing ropes and carabiners (climbing hooks) all over the floor, a cooking pot and boxes of Clif energy bars. “A lot of climbers live in their vans. It’s just easier.”

It’s a rape van, Alex.

“But it’s good for both lifestyles, climbing and raping,” he says. “I’m more into climbing.”

He’s up at seven the next morning, painting white antihydral paste on his fingertips, to stop them sweating, and sanding down any loose shreds of skin. His hands, he says, are his only physical advantage: “The skin is basically indestructible. I never get cut.”

Incredibly, on the day after finishing the Triple, he’s about to climb again. Only it’ll be “supermellow” this time, nothing “extreme” or “hardcore” - just a photoshoot with a sponsor, the climbing gear brand, Black Diamond. He has six sponsors – The North Face, Black Diamond, La Sportiva, Clif, New England Ropes, and recently, Ball Watch, a luxury watch company, which gave him a $3000 watch. “I feel like a total douche,” he says. “That thing’s worth more than my van.”

Honnold has a purist’s suspicion of marketing departments and PR. He’s not at all seduced by what he calls “the bullshit”. But his sponsors provide him with a salary and a travel budget, which given his simple needs, affords him a lifestyle that is, he says, “pretty fucking awesome.”

Last year he travelled to – in receding order - Morocco, England, France, Spain, Chile, Mexico, Poland and Canada. The year before was Chad, Jordan, Israel, Turkey, Greece, China… it’s a long list. He mostly goes where he wants, when he wants, with no strict agenda, and in between, he lives in his van, climbing all over the US and crashing occasionally at his mom’s place in Sacramento, his only permanent address, where he spends “maybe 14 days per year.”

Were he a materialist, he might milk his fame, and pursue a van sponsor, say. But he’s not. “This van works fine,” he says. “And we’re way too consumerist in this country, anyway.” Besides, he doesn’t much enjoy being a celebrity. “It’s funny to get sick of people telling you how inspiring you are, you know? I mean, it’s just rock climbing. I didn’t save the world.”

You’re not proud of your achievements?

“No, I am, I guess, but that’s what I do. I’m a climber. Everyone’s got their thing. I could never hit 30 free throws in a row, but a basketball player would think that was trivial.”

Lebron doesn’t die if he misses, I tell him. Free soloing and free throws aren’t the same. One takes courage. It’s like his fans say on his comment threads: ‘it must be hard climbing with balls that big.’

He grins. “The balls part is true. They are pretty freaking huge. But I wouldn’t say courage. Courage is doing something that you don’t want to do, like a soldier. I want to be half way up a mountain. I think it’s awesome.”

In fact, while we’re at it, there are a few misconceptions about free-soloing that he’d like to address. Firstly, he only free solos a few times a year – most of the time he uses ropes like everyone else. Secondly, he’s not risk-addicted and he doesn’t have a death wish. And thirdly, it isn’t that dangerous anyway.

“Look, I wouldn’t free solo something that I wasn’t confident about. I want to play with my grandkids. I’m saving for my retirement. The reason I do these long solo climbs is because it’s a cool way to climb. I like the simplicity. You don’t have any gear on you, you don’t have a partner, you move faster.”

One of Honnold’s heroes, Peter Croft talks about flow. Croft was the first man to free solo the Astroman wall in Yosemite (5.11), among other accomplishments. “I compare it to a runner’s high,” he says. “With ropes and a partner, you’re always being interrupted, but with free soloing, you can just go. It’s just you on the rock reacting to what’s going on. I’m so focused that when I get to the top, everything looks different, the colors, the light.”

Honnold is less poetic. “I’m more focused, for sure, but it isn’t like all of a sudden the harps strum and you’re in some magical state.” A self-described militant atheist who exclusively reads non-fiction, he isn’t inclined to rhapsodize. As he drives from one wall to the next, he points at the road. “Look, I’m at risk of dying right now.” And he’s right - he’s slaloming around mountain bends, steering with his knee, checking his iPhone with one hand and eating a banana with the other. “Driving is probably the most dangerous thing I do. One momentary lapse and we’re both dead. We’re always at risk. And we’re all going to die eventually anyway, so you may as well lead the life you hoped to lead.”

Not all climbers agree. Tommy Caldwell is one of the world’s best –Honnold describes him as “a much better climber than me” - and he doesn’t mince his words. “I think what Alex does is amazing but I will never free solo. I’ve fallen unexpectedly many times on easy pitches and if I didn’t have a rope, I’d be dead.”

Before Honnold climbed the Triple alone, he free-climbed it with Caldwell, and during that climb, Caldwell fell twice. “Alex just says, ‘that’s never happened to me…’ And I think that to be that good, you have to think that way. Alex and Peter have this calm way about them – they don’t see free soloing as some conversation with death or enlightening experience. But the fact is, most serious free soloists die. And they die on easy pitches, not hard ones.”

According to Outside magazine’s David Roberts, in the last 40 years, nine Americans have raised the bar on free soloing, and five are now dead. The most recent was John Bachar in 2009, a close friend of Croft’s, who died on a route he’d free soloed many times before.

“I know the risks,” says Honnold. “I’ve fallen sometimes when I haven’t expected to, with a rope on, too. But that’s with a rope, you know? I trust myself that, when it really matters, I won’t fuck up.”

All Alex ever wanted to do was climb. His mum Deirdre says, “even as a toddler, he always wanted to be high up. I’d turn my back and he’d be on top of the refrigerator or the closet.” His dad would take him to the local climbing gym in the suburbs of Sacramento, and the obsession took hold. So much so that come his first year at the University of Berkeley, he placed 2nd in the youth national rock climbing championships and was looking forward to the world championships in Scotland later that year.

That was the year it all changed for Honnold. His folks were both teachers, and he’d aced high school, but he had no interest in college. He hardly showed up for lectures. Then his dad died of a heart attack, leaving Alex with a chunk of money, supposedly to finish his education. But Alex had other ideas. “Dad was part of the pressure to go to college in the first place. So suddenly, he’s gone, I have this opportunity to go to Europe and enough money to live on the road for a while…”

He did poorly in Scotland, coming 39th. But when he returned, he knew what he wanted. His Mom gave him her Chevy Minivan, and for two years he drove around the American West climbing with whomever he could find. And where he didn’t know anyone, or was too intimidated to make friends, he climbed alone.

“I must have free soloed thousands of pitches,” he says. “And I had all kinds of fucked-up experiences, climbing the wrong route, and getting really scared. But I learned that, to a large extent, the cruxing was self-imposed”. “Cruxing” is climber-talk for those moments of difficulty, fear and panic – those times when, as Honnold says, “you go ‘I’m scared, I’m really scared, oh God oh God oh God…’”

He emerged from this period in 2007 as a world class free soloist, conquering big walls in times that made the climbing community sit up and take notice. And then he scaled Half Dome in September 2008, an ascent which so captured the imagination that it essentially launched him as a pro-climber.

Half Dome has also given Honnold perhaps his most gripping climbing story. It was a moment towards the end when he was cruxing badly on a smooth slab at an 80 degree incline. There were just no good holds available. At his level, he’d happily put all of his weight on an edge as slim as a dime so long as it was sharp, but all he could find were smooth, rounded dimples. Could he trust them? If he slipped, nothing would stop him from sliding down the slab and falling to his death. And yet he was so close to the peak - he was 1900ft up - that he could hear the tourists at the top.

“I’d been stuck in that position when I practiced it, that was the thing,” he says. “I just thought I’d find another way when the time came. But I couldn’t. So I started trying all these other little footholds and rejecting them, because they were even worse.”

There was, however, a bolt within reach, with a big carabiner attached, left by a previous climber. He could easily grab the carabiner and hoist himself up. “But I didn’t want to climb all the way up there only to cheat on one move. And at the same time I was like, ‘how fucking dumb would it be to slide off this mountain when there’s a carabiner right there?’”

In the end, he compromised. Heart racing, breath-quickening, he touched his finger on the bolt, so that if he started slipping, he could grab it. He didn’t need to in the end. And he emerged at the top, pumped and shirtless.

“It was so surreal. I was all stoked, and all these people were up there eating sandwiches and talking on cellphones. They didn’t even notice me because I didn’t have any climbing gear on. I just looked like some idiot who got lost. So I just took off my climbing shoes and started hiking down. And then all these people came up to me saying, ‘woah you’re hiking barefoot! That’s hardcore!’ I was like, ‘whatever dude. You have no idea.’”

The ‘supermellow’ day of shooting turns out to involve hiking up to the rock face, climbing, hiking down, and then doing it again at another face. And another, and another, until sunset. For this soft-bellied suburbanite, the hikes alone are murder. But Honnold is having fun. He laughs when the Black Diamond Team ask him to wear a helmet, he laughs: “I know I’m all about safety first, guys, but this is retarded.” He wears it anyway and spiders easily up a wall that has just turned to gold thanks to a sunset that, by common consensus, is not only sick but heinous.

At the top, Honnold flexes his muscles. “Do you want me to diddle my nips too? Photographers love it when you stimulate your nipples.”

By nightfall, we’re back in his van, heading back to my hotel. He’s just dropping me off there, he doesn’t have a reservation. The Black Diamond team is staying elsewhere. Only Honnold, the star athlete, is without a proper room for the night, not that he cares. He’s talking about his summer plans. Maybe he’ll hit the road with his girlfriend of two years, Stacey - on top of his other accomplishments, it seems Honnold has also found a girl who’s cool with living in a van for months on end. “Well… yeah,” he says. “But I tend to break up with her at least once a year.”

As we wend through the forests, the immensity of El Capitan looms above us. It’s a rock he knows intimately, every route, every crevice. I push him on whether he’ll free solo that this year. He won’t say. But he won’t rule it out.

We pull into the car park. He looks pleased. It’s an easy place to park for the night – plenty of room, no watchmen to give him hassle.

“You see?” he says. “Not everything in my life is super-intense. Sometimes I just do these boring photoshoots all day. I swear a lot of the aura around my life is shit that people project onto it. The truth is way less exciting. Your article should say, ‘I met this dude, he’s totally mellow and he trains real hard and climbs quite well. The end.”’

OK, Alex. I’ll say that.

“Oh and dude, can I get a quick shower in your room, and charge my laptop?”